Advertising

From Pink Slips to Silent Sidelining: Inside adland’s layoff and anxiety crisis

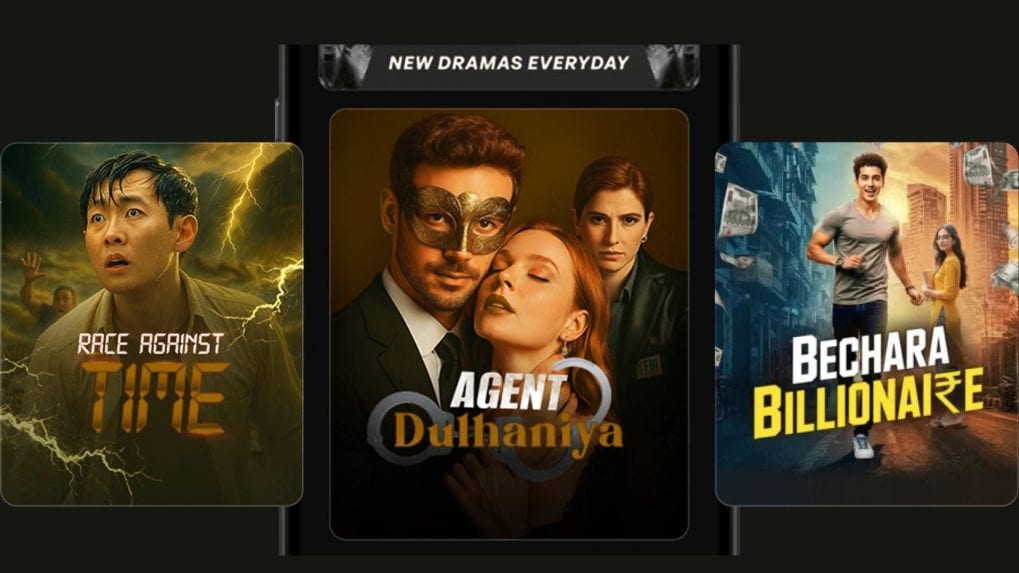

When the micro-drama wave first hit India, it was sold as a democratic, creator-friendly format. Short episodes, mobile-first viewing and quick production cycles promised opportunity for a new generation of writers and filmmakers. But behind the boom, a quieter crisis is unfolding.

Writers say the space has turned into a race to the bottom.

“Nothing short of obnoxious”: the data behind the discontent

Sulagna Chatterjee, founder of the community Women Film Circuit, has been collecting anonymous testimonies from writers to formally take the issue to the Screenwriters Association (SWA). So far, she says, they have gathered around 60 responses and 80 signatories, including veteran writers and directors.

“What is happening is nothing short of obnoxious,” she says.

Her survey findings challenge the assumption that micro-dramas are being written only by beginners. According to the data:

35.1% of respondents have five years of experience

29.8% have six to ten years

22–23% have over ten years

Only 12.3% have zero to two years

“This is not a space dominated by newcomers,” she says. “Experienced professionals are being pushed into this market because long-form opportunities are drying up.”

The payment figures, she says, are stark:

66.7% were paid less than Rs 50,000 to write a micro-drama of 60 to 100 minutes

28% were paid between Rs 50,000 and Rs 75,000

“That means almost 90% of the market is earning under Rs 75,000 per project,” she points out.

Timelines are equally punishing. According to her survey:

57.9% were given less than two weeks to deliver

81% had no cap on revisions

72% had no written contract

Only 22.8% were paid on time, while 26% faced delayed payments and 10% received only partial payments

Yet, she acknowledges the irony. “Platforms like Pocket FM, Kuku, Bullet and others have substantial financial backing. But there is very little willingness to invest in writers.”

“45 episodes in three days”: the writer’s reality

Micro-drama writer Sohini Mukherjee says, “Right now, I am writing 45 to 50 episodes for a micro-drama project, and I am being paid only Rs 20,000 to Rs 25,000 for the entire assignment.”

The timeline? “I have to deliver the first draft of all 45 episodes within three to four days. After that, revisions start. But the initial delivery has to happen in that extremely compressed timeline.”

Creative control, she says, lies largely with platforms. Earlier, writers worked directly with channels, but now production houses sit in between. “When dealing directly with a channel, at least there is a proper contract and a standard payment structure. But once a production house enters the picture, the writer’s share drops further – to Rs 30,000 or even lower.”

She refuses to accept the logic that desperation should dictate pay. “If someone else is willing to do the same work for less, they will still deliver the same quality. The more money you invest, the better the output will be. Quality and compensation are directly linked.”

“A feature film in a five-lakh budget”: producers push back

For auteur producer Nilakshi Sengupta, the problem goes beyond writers alone. She entered the micro-drama space in December last year, intrigued by the format. What she found instead were impossible economics.

“In micro-dramas you are making a 90-minute story divided into about 45 episodes. Ninety minutes is a full feature film. And a feature film requires scale,” she says.

A basic two-day corporate shoot, she explains, costs six to seven lakh rupees for just 3 to 10 minutes of content. “Here you are expected to make a full narrative series in budgets of five to ten lakh rupees. How is that even possible?”

Her breakdown is simple:

A proper location alone costs Rs 40,000

You need multiple locations

Crew: cameraman, assistants, lighting technicians

Post-production alone costs around Rs 2 lakh

Then dubbing, sound, editing, colour correction

“And after all this, if I as a producer can’t even make Rs 50,000, what is the point?” she asks.

She also describes questionable practices. “Yes, I have heard about platforms scamming writers. They ask for detailed concepts, avoid paperwork, and then simply disappear.”

Her conclusion is blunt: “This model is not sustainable. Right now the entire ecosystem is driven by numbers, not by quality.”

A rare exception

Interestingly, not all experiences are negative.

An anonymous writer who worked with Kuku FM says they were paid Rs 2.5 lakh for an entire series – an amount considered unusually high by current standards. “It was one of the better-paying projects I’ve done,” the writer said, requesting anonymity.

Such cases, however, appear to be exceptions rather than the rule.

Actors see a different picture

From the acting side, the experience looks very different. Actor Avinash Bhargava, who has worked across multiple micro-drama platforms, says payments for actors remain relatively stable.

“For known TV actors, the payment usually goes up to Rs 50,000–60,000 per day,” he says. On one project for Kuku with a budget of Rs 25 lakh, he worked for four days at that rate.

Even non-television and theatre actors, he says, are being paid around Rs 50,000–60,000, and “they generally refuse to work for less.”

He admits, however, that budgets are shrinking. “Many productions operate on Rs 12–15 lakh budgets now. Shoots are compressed into two days plus half shifts. That puts enormous pressure on everyone.”

Still, he believes the format is here to stay. “People no longer have patience for long shows. Micro-dramas are addictive. Subscription models of Rs 30–100 are working, especially in Tier-2 and Tier-3 markets.”

His forecast: “The sector will survive for at least the next five to six years.”

“90% are not professional writers”: a consultant’s take

Founder of MangoScripts Manish Jaiswal, who represents more than 500 writers, offers a more industry-focused explanation.

“About 90% of micro-drama writers are not professional writers,” he claims. “Many come from non-industry backgrounds like housewives and college students.”

Among the writers he manages, however, 80–90% are professionals. He says many entered micro-dramas only after long-form work began drying up in early 2025.

“At first, platforms paid decently – around Rs 80,000 to Rs 90,000 for a show. A writer could finish one or two projects a month,” he says.

But competition changed everything.

“Rates dropped from Rs 80–90k to Rs 50k, and now many platforms pay only Rs 25,000–30,000. If four writers refuse, platforms simply find four others.”

He describes brutal timelines: scripts demanded within six days, full projects completed in two weeks, shoots in two days and edits in five.

Budgets, he says, often range between Rs 10–12 lakh, yet writers receive less than Rs 50,000, even though they should ideally be getting Rs 1–1.5 lakh.

“In traditional cinema, SWA guidelines say writers should get 3–4% of the total budget. In micro-dramas, there are no regulations at all.”

Some platforms like Stage OTT still pay around Rs 75,000, he says, but others – including Cuckoo TV and Pocket TV – have pushed rates down sharply.

A booming format with broken foundations

Micro-dramas are booming because audiences want short, mobile-friendly content. Platforms are earning through low-cost subscriptions and massive user bases.

Yet the very people who create these stories say they are being squeezed out.

As Chatterjee prepares to formally take her findings to SWA, the central question remains: can an industry built on underpaid writers and impossible timelines truly sustain itself?

Right now, the numbers tell a troubling story.

From purpose-driven work and narrative-rich brand films to AI-enabled ideas and creator-led collaborations, the awards reflect the full spectrum of modern creativity.

Read MoreLooking ahead to the close of 2025 and into 2026, Sorrell sees technology platforms as the clear winners. He described them as “nation states in their own right”, with market capitalisations that exceed the GDPs of many countries.