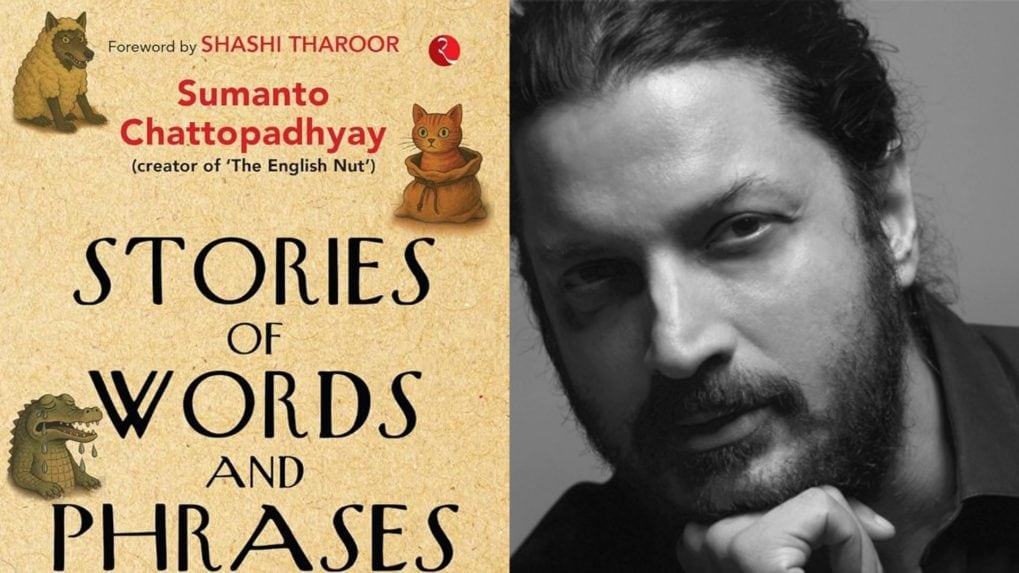

Sumanto Chattopadhyay’s ‘Stories of Words and Phrases’ unveils the origins of everyday expressions

Sumanto Chattopadhyay, former Chairman and Chief Creative Officer of 82.5 Communications, renowned wordsmith, and creator of the award-winning social media channel The English Nut, delves into the rich histories of everyday expressions—from boycott and Bluetooth to phrases like rest on your laurels—in his book, Stories of Words and Phrases.

ADVERTISEMENT

It’s well-known that Sumanto Chattopadhyay, former chairman and chief creative officer of 82.5 Communications, is a wordsmith, a talent reflected in his recently published book, 'Stories of Words and Phrases'. As the creator of The English Nut, an award‑winning social media channel with weekly videos about vocabulary, etymology, grammar and usage, Chattopadhyay transformed his passion project into a polished anthology that dives into the origins and stories behind expressions or phrases used in everyday lives.

In Chattopadhyay’s words, “What started as a simple passion project—a way to share my love for words—soon found an audience of fellow ‘verbivores’. Together we celebrated language for its quirks, its unpredictability and its depth.”

Shashi Tharoor, former diplomat, author and a renowned linguaphile, penned an insightful foreword for the book—an endorsement that itself exemplifies his mastery over English. In his praise for Stories of Words and Phrases, he reflected on the countless hours of voracious reading he undertook to cultivate his own command of the language, a practice that shaped his identity as a maniac wordsmith.

From the earliest pages of his book, Chattopadhyay fondly recalled how his parents first introduced him to the dictionary—an act that sparked his lifelong fascination with words. This early exploration sowed the seeds of The English Nut, shaping the world where readers could uncover the rich backstories behind everyday words and phrases.

Let us take for example ‘Boycott’, whose origins trace back to Captain Charles Boycott, a land agent in 19th century Ireland who was socially ostracized during a rent dispute. In Chattopadhyay’s words, his name soon became a ‘verb’, and it is commonly used without any thought.

Who does not dread hearing the word ‘Deadline?’ Beginning as a literal line for prisoners who couldn’t cross without risking being shot, today, it simply means a ‘due date’.

Was it a known fact that ‘Bluetooth’, which connected phones to our ear buds or helped in quick transfer of files, was originally the nickname of a tenth-century Danish king.

Read More: Brand Blitz Quiz: Here are the contenders for the regional finals

“These transformations remind us that language is a lens through which we view the world, and that lens is constantly being polished, scratched and refashioned,” Chattopadhyay added.

When one hears the word ‘Blockbuster’ or we come across a news piece celebrating the ‘blockbuster success or run of the film in the theatre’, we associate it with the world of entertainment. And, also to sports and politics. However, the word’s first appearance was in the American TIME magazine, in a 1942 article on the Allied bombing of key targets in Fascist Italy.

The book also documented the different meaning of ‘blockbuster’, which refers to a real estate broker or speculator who sells a house in an all-white neighbourhood to an African-American family, thus leading to an exodus of white families, and causing housing prices to decline. The broker, who then profits from this racism-driven market instability is called a blockbuster. The practice is called ‘blockbusting’.

Con, in Chattopadhyay’s words, is a slang abbreviation for ‘confidence’. To con people is to defraud them by exploiting their compassion, vanity or greed, after gaining their confidence. However, ‘con’ is also a slang abbreviation for ‘convict’, which is what the con artist becomes if he or she gets caught.

‘Malaria’s origins are from ‘malus aria’ in Latin or ‘mala aria’ in Italian, with a common meaning being ‘evil air’. Malus is the Latin word for ‘bad’ or ‘evil’, and ‘Mala’ means the same in Italian. ‘Aria’ too shares a common meaning in both the languages meaning ‘air’.

Read More: Storyboard18 x The English Nut: How to pronounce these 10 brand names

For centuries, people mistook that it was caused by foul vapours that rose from marshy lands. Hence, ‘swamp fever’ was another name given to malaria. “The term malaria was probably introduced by Italian physician Francesco Torti (1658–1741) in the eighteenth century,” the book highlighted.

A cuddly bear also known as ‘Teddy Bear’ originates from the experiences of the 26th US President Theodore Roosevelt, who was invited to a bear hunt in Mississippi by Governor Andrew H. Longino. When his attendants caught injured, and tied an American black bear to a tree, Roosevelt could not bring himself to shoot the bear down.

“This story spread like wildfire and, on 16 November 1902, it became the subject of a political cartoon in Ne Washsnglon Posl. Drawn by Pulitzer prize-winning cartoonist Clifford Berryman, it depicted a bear lassoed by a handler as the president looked on in disgust. While this original cartoon featured an adult black bear, in later drawings it was replaced with a younger, cuter bear,” reflected Chattopadhyay in the book.

We owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Morris Michtom, a Brooklyn candy-shop owner—and his wife Rose—who, inspired by the cartoon, crafted a small plush bear cub. Displayed in their shop window under the sign “Teddy’s Bear”—with “Teddy” being Roosevelt’s familiar American nickname—the bear was an instant sensation.

This humble invention did more than launch a stuffed‑toy revolution: it transformed public perception of wild bears, shifting them from fearsome creatures to symbols of comfort and innocence.

It is known that ‘Rest on your laurels’ signifies being satisfied with past successes, and striving for new achievements. During ancient times in Greece and Rome, people who achieved distinction were honoured with a laurel wreath, which was made with the leaves of the aromatic Laurus nobilis tree, also known as Sweet Bay.

As per the book, the tradition of laurel wreaths could be traced back to the Pythian Games held every four years from 582 bCE to 394 CE in the city of Delphi in ancient Greece. Besides athletic competitions, the event also showcased a range of performing arts.

Participants were crowned with a laurel wreath for their outstanding performances in acting, dancing, painting and music. The Pythian Games were held in honour of the Greek god Apollo, who was associated with the laurel wreath. According to Greek mythology, he was in love with the nymph Daphne. But when he approached her, she turned into a laurel tree.

“Undeterred, Apollo embraced the tree and wore a wreath of leaves plucked from it,” highlighted in the book.

The book unravels several other fascinating stories behind everyday expressions, and for Chattopadhyay, this is just the beginning of introducing readers to the rich historical contexts behind the words and phrases we use daily.

Read More: Sumanto Chattopadhyay to retire from 82.5 Communications