Laura Spinney: Proto is a tale out of linguistics, archaeology and genetics

Laura Spinney, author, Proto, in a conversation with Storyboard18 added, "I had to remember that my subject was language and therefore linguistics had to lead the way."

ADVERTISEMENT

Everything that is invented or discovered, needs a name. Otherwise what will people call it? And as people travel, the words they use travel too. This is how language spreads. And the language that spread from a handful of people at first, to billions by usage, is ‘Proto-Indo-European.’

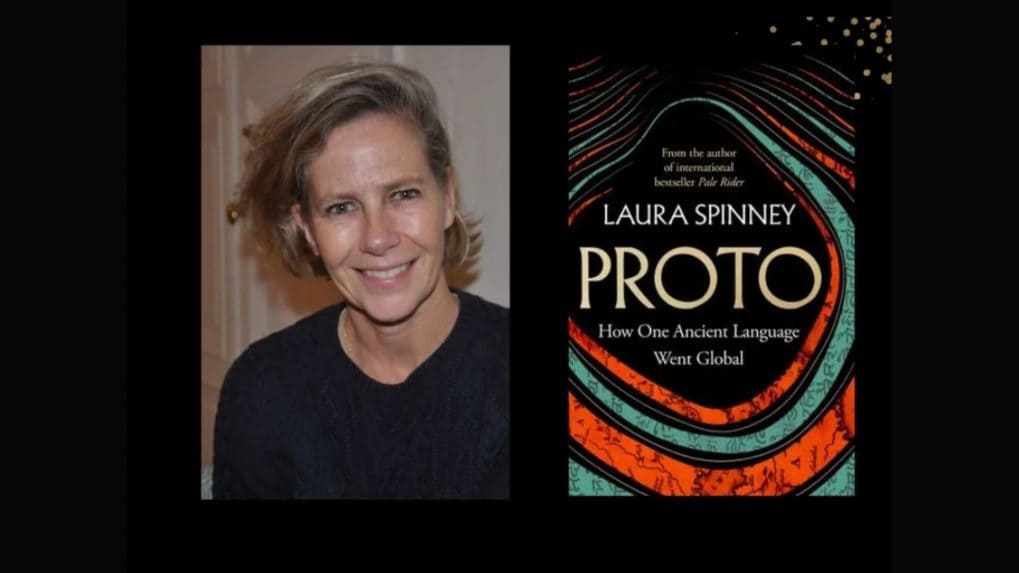

Author Laura Spinney has written a book called ‘Proto’ to trace this. This is not her first book; she has two novels, 'The Doctor' and 'The Quick’, and a collection of oral history entitled ‘Rue Centrale,’ research papers and translations to her credit.

In a conversation with Reeta Ramamurthy Gupta, Spinney talks about her work and passions.

Excerpts

You say that language is “humanity’s oldest tool. “I couldn't agree more. Your trigger for the book seems to be science - DNA extraction and analysis - or paleogenetics. How challenging has it been for you to maintain a multidisciplinary balance while tracing linguistic development?

It’s a book about language, as you say, but the language in question predated the invention of writing, meaning that it can only be studied indirectly because there are no texts preserving it. Since language is a means by which we convey ideas and knowledge, the story leans heavily on archaeology – another way of tracking ideas and knowledge, through material culture. But it also draws on genetics, because very often it is people who carry languages far and wide, causing them to change in the process. My task was to weave a tale out of linguistics, archaeology and genetics, always remembering that my subject was language and therefore linguistics had to lead the way.

Language is political. It is tied to identity. The Indo-European story has been used and abused, you say. Was correcting the narrative, one of your goals with the book?

Language is political by definition. A language is a dialect with an army and a navy, as someone witty once said. I’m not sure it is for me to correct the narrative – or frankly, that anyone would listen if I did – but I did want to show that there was a long history of people distorting the Indo-European story for their own political ends, and that it’s still happening today. There is much uncertainty in that story, but if a politician is saying “x is true” and the scientists are saying “we can’t possibly know if x is true,” then you have a problem. You need to be wary.

Your book is authoritative. Thankfully so, because you're clearly concerned about misrepresentation and keep linguistics in the forefront. What were the gaps that bothered you the most, when you went about writing this?

There are so many gaps! I’m not sure that any of them bothered me, as such, since that is the nature of the beast. If you are discussing a time before writing, then by definition you are not engaged in the same task as a historian – you have other sources at your disposal, which allow you to say or not to say different kinds of things. Without writing, for example, there’s very little you can say about character. There were times when I would have loved to know what a prehistoric person was like, or what they thought, but that information was definitively beyond my reach.

Read More: Bookstrapping: Literary tribute to French novelist Marcel Proust

Have readers written to you with their views? For eg; you speak of Dante's work, 'The Divine Comedy' being written in the Italian Vernacular as 'hastening' the death of Latin. But would you agree that the fall of the Roman empire and the inhabitants abandoning the cities and towns, moving to the countryside, was an important a reason for this? In terms of timelines, this was so much earlier than Dante. Was Dante's choice also a 'consequence' and not only a cause'?

Yes readers have written to me with their views, which is great – especially when this is a story with so many unknowns and with such a strong political dimension. On Dante, the fragmentation of Latin began even before the fall of the western Roman Empire, since the dialects spoken across that empire would have diverged as it expanded. The “fall”, though hard to pinpoint in time, would have accelerated that process, and so – in a different way – would Dante’s spectacular showcasing of his Tuscan dialect. As I wrote, Latin had already been shuttered into places of learning by then. It takes many blows to kill a language.

I was pleasantly surprised to catch Nick Patterson, a mathematician with a yen for computational genomics, in the book. Laura has gone far out, while integrating voices that matter. Which is why she says, “perhaps the subjects choose me. I go where the inspiration takes me!”

Reeta Ramamurthy Gupta is a columnist and bestselling biographer. She is credited with the internationally acclaimed Red Dot Experiment, a decadal six-nation study on how ‘culture impacts communication.’ Asia's first reading coach, you can find her on Instagram @OfficialReetaGupta.