“Dessert mixed with pharmacy-grade caffeine”: Himatsingka slams Sting, Red Bull, Monster

Himatsingka highlighted the caffeine and sugar levels contained in these drinks, suggesting they can pose risks to young consumers.

ADVERTISEMENT

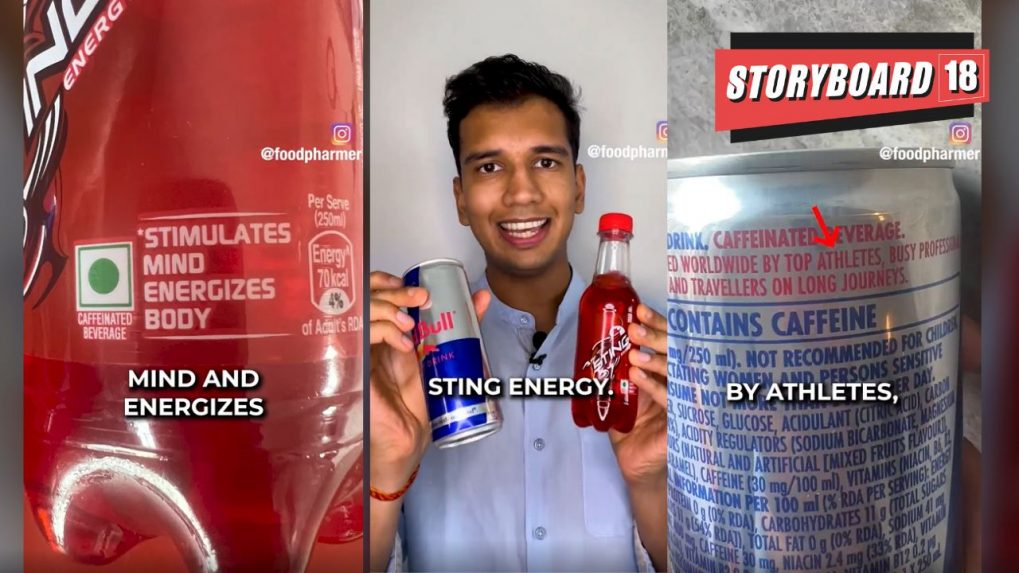

Health and nutrition influencer Revant Himatsingka, popularly known as Foodpharmer, has once again stirred debate in India’s food and beverage industry. After making headlines with his viral takedown of Bournvita earlier this year, Himatsingka has now raised an alarm over the growing popularity of energy drinks such as PepsiCo India-owned Sting, Red Bull, and Monster among children and teenagers.

In a strongly worded LinkedIn post, Himatsingka pointed out what he sees as a troubling contradiction. “Energy drinks like Red Bull and Sting Energy write ‘not recommended for children’ on the bottle. But ironically, they’re most popular among children,” he said.

He went on to describe how these products have become a common sight across India. “Because Sting, Monster, Red Bull… they’re everywhere now. From cricket nets to paan shops outside schools. And it’s not 25-year-olds drinking them. It’s teenagers. It’s kids.”

Himatsingka highlighted the caffeine and sugar levels contained in these drinks, suggesting they can pose risks to young consumers. According to him, a 250 ml bottle of Sting has 72 mg of caffeine, while Red Bull has 80 mg. Monster, the global energy drink giant, contains as much as 160 mg of caffeine in a single can.

The sugar content, he argued, makes the situation even worse. “Add the sugar on top: 17.5 g in Sting + artificial sweeteners, 27 g in Red Bull, 54 g in Monster. You’re basically handing kids dessert mixed with pharmacy-grade caffeine and calling it ‘energy,’” he wrote.

The lure of marketing

Beyond the nutritional profile, Himatsingka criticised how energy drinks are branded and marketed, suggesting they deliberately appeal to younger consumers. “And the packaging is the smartest (and scariest) part. Neon colours, cool taglines, gamer branding. ‘Vitalizes body and mind.’ Tell me honestly, which 14-year-old is going to stop and read the tiny line that says ‘Not recommended for children’? I’ve literally seen 13-year-olds treat it like an everyday drink. That’s how normalised this has become.”

The influencer also questioned the regulatory oversight of energy drink sales in India. While Punjab has banned them around schools and Maharashtra has attempted restrictions, he said enforcement remains weak. “And the rules are patchy at best. Punjab banned them around schools. Maharashtra tried restrictions. Labels say ‘high caffeine.’ But there’s no age gate or real enforcement,” he observed.

Himatsingka cited industry data to underline the scale of the issue. “India drank 570+ million litres of energy drinks in 2023, and the industry is headed towards a billion-dollar size, and we’re letting it grow on the backs of kids who don’t even know what 160 mg of caffeine does to their body.”

He also pointed out the potential health risks beyond the short-term “energy” boost often advertised. “Forget wings… these cans give you anxiety, sleep loss, and sugar crashes,” he cautioned.

Calling for stricter regulation, Himatsingka drew a comparison with alcohol. “So if you can’t buy alcohol without an ID, you shouldn’t be able to buy an energy drink either. Because at the end of the day, it’s about young hearts and young brains, and they deserve better!”

Previous campaigns against food brands

This is not the first time Himatsingka has clashed with large food and beverage corporations. In May, he released a viral video highlighting the high sugar levels in Mondelez India-owned malt drink Bournvita, challenging its branding as a “health drink.” The video drew widespread attention, forcing a national conversation around sugar consumption in packaged foods. Mondelez responded by sending Himatsingka a legal notice, prompting him to take the video down.

However, the controversy had already gained momentum, with millions of netizens rallying behind his claims. The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR), India’s apex body for safeguarding child rights, later directed Mondelez to review and withdraw all “misleading” advertisements, packaging, and labels associated with Bournvita.

Himatsingka has also publicly criticised other popular brands for their sugar content, including Hindustan Unilever’s Kissan Tomato Ketchup and Nestlé India’s Maggi Tomato Ketchup.

His latest campaign comes at a time when India’s food and beverage sector is witnessing exponential growth in the energy drinks category. With projections indicating the industry could reach billion-dollar valuations in the coming years, concerns about health impacts—particularly among children—are only intensifying.

Read More: Food influencer Foodpharmer calls out PepsiCo for taking down video on Sting energy drink

Read More: After Bournvita, influencer 'Foodpharmer' goes after Kissan and Maggi ketchup