Micro-Dramas have viewers hooked, but FMCG brands are still on the fence

For India’s biggest advertisers, especially FMCG brands, micro-dramas remain a space of curiosity rather than commitment.

ADVERTISEMENT

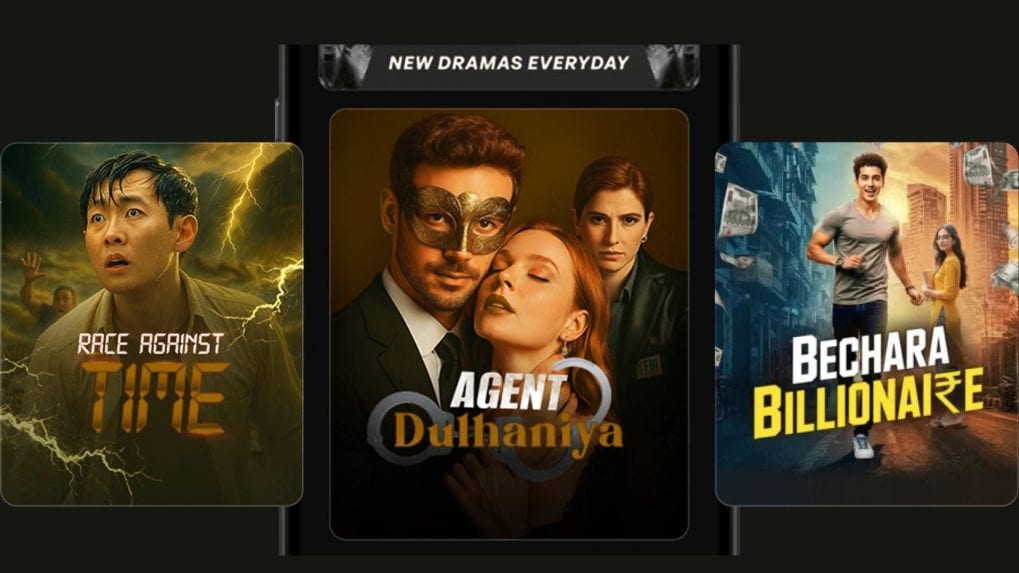

Micro-dramas are everywhere. Scroll through Instagram, YouTube or any short-video platform and you will find endless bite-sized episodes – love triangles, family feuds, office romances – packaged in 60 to 90 seconds.

For audiences, they have become a daily habit. For platforms, they are turning into a serious business. But for India’s biggest advertisers, especially FMCG brands, micro-dramas remain a space of curiosity rather than commitment.

“The companies I am involved with have noticed that microdramas have reached a point of inflection. They are growing dramatically. Dedicated platforms like Pocket TV, and others have become big players. Platforms like DramaBox and ReelShort are also seeing strong traction,” says Lloyd Mathias, angel investor and independent director.

“For consumers, microdramas have become like a short snack. In between jobs or daily activities, people are watching a few episodes. JioStar is rolling out a dedicated microdrama vertical sometime in the first quarter of this year. So it is becoming a very big play. This growth is quite expected.”

Mathias points out that India is following a familiar curve. “China went through the same phase about four or five years ago.” Yet, despite the surge in consumption and platform investment, big advertisers are not rushing in.

“At the moment, brands are largely in a wait-and-watch mode. One reason is that this is a very short format. You are talking about 60 to 90 second dramas. Brands are still trying to understand how advertising will fit into such a short, fast-moving format,” he explains.

Some experimentation is happening, but cautiously. “What is already happening is branded micro-series. Brands like Myntra have already done a few micro-series. A lot of brands are also looking at integrations – where a product or brand appears inside the story itself through a character or a setting. That kind of integration is already taking place.”

Traditional advertising, however, is still a grey area. “Brands are waiting to see whether there is real advertising acceptability in such a short format. They are asking: if you insert ads into a 60 to 90 second episode, will viewers see it as an irritant?”

For now, most brands prefer softer routes. “Right now, many brands are approaching microdramas through sponsorships or integrations rather than traditional advertising.”

When asked why large FMCG companies with deep marketing budgets don’t simply create their own micro-drama series instead of spending on expensive celebrity campaigns, Mathias is blunt.

“I would say brands are not really in the business of creating entertainment content. Brand marketers know how to sell, distribute and advertise a product. Creating original entertainment is a very different skill set.”

There is also a structural limitation. “Microdramas are very hyper-local. Popularity often varies from region to region. Sometimes a microdrama becomes popular only in a specific part of a state or a very small geography. For a national brand, it becomes difficult to get the kind of reach they need through such fragmented content.”

Because of that, he believes mass brands will continue to lean toward safer, proven channels. “Brands will continue to lean more toward large influencers and broader platforms to get mass reach.” The biggest risk, according to him, is viewer backlash.

“Marketers are cautious because inserting an ad into such short content can feel very intrusive. When people are watching a 60 to 90 second episode and an ad suddenly comes in, it could feel like an irritant. It is similar to watching cricket – between the bowler bowling and the batsman batting, if an ad pops up, viewers get annoyed.”

Does that mean micro-dramas may never become a serious advertising medium? According to Mathias brands are waiting and watching. They will eventually find interesting and innovative ways to be present. But I believe integration and sponsorship will be far more effective than traditional banner ads or interruptive advertising,” Mathias says.

“Brands are more likely to sponsor entire micro-series or integrate themselves naturally into the storyline rather than run standalone ads.”

Interesting, But Complicated

For FMCG marketers, the appeal of micro-dramas is obvious but so are the risks. “Micro-dramas are interesting for FMCG brands because they sit at the intersection of storytelling and everyday life,” says Akshali Shah, Executive Director, Parag Milk Foods.

“These formats often mirror real household settings and routines, which is where food and dairy brands naturally belong without the need for overt or forced messaging.”

But Shah makes it clear that engagement alone is not enough to unlock budgets. “The ecosystem is still evolving. For large FMCG companies, participation is not just about visibility or reach. Brand safety, the tone of content, suitability for family audiences, and clarity on impact measurement are equally important considerations.”

Even when audiences are present, FMCG brands move slowly and carefully. “We are seeing strong consumer engagement on these platforms, making it a space worth observing closely. Any brand integration, when it happens, has to feel organic, reflect how consumers genuinely interact with our products, and align with the trust we’ve built over time,” she adds.

The Data Problem

Another reason FMCG advertisers are hesitant is that micro-dramas do not yet fit neatly into conventional media planning frameworks.

“While microdramas have been booming recently, it is true that currently its share of advertising revenues is not commensurate,” says Samit Sinha, Managing Partner at Alchemist Brand Consulting.

He lists three reasons. “The audience for microdramas is fragmented. The audience is more from Tier 2 and 3 towns. And media agencies are still working on the audience data in terms of ascertaining the size, distribution and consumption habits of the audience.”

In other words, there is excitement but not enough reliable measurement.

Still, Sinha believes the situation will change. “It is still early days and we should expect significant adoption by big advertisers in the coming months.”

ROI Over Everything

For large FMCG companies, the core issue is not creativity but accountability. “FMCG brands are adopting a wait-and-watch attitude to micro-dramas,” says Nisha Sampath, Brand Consultant.

“While short video consumption is very high in India, consumption alone cannot address their core question – whether investing in this format can drive brand equity and sales.”

Unlike a standard campaign, micro-dramas require long-term commitment. “As a marketer, unless you commit to multiple episodes you won’t come to know if the story is working or not. The unpredictability and novelty of the medium makes it seem less like a safe bet.”

Traditional ROI models also struggle to keep up. “Standard FMCG ROI models prioritise metrics like attribution, cost-per-reach, or sales, which are harder to measure with micro dramas. Proof at scale of whether it works is limited in India, unlike in China where micro dramas attract serious capital investment.”

There is also a talent and ecosystem gap.

“Micro-dramas demand an entertainment-style production and distribution logic. Unlike ad campaigns, they need episodic writing, character arcs, rapid iteration, and platform-native thinking.”

That is why early movers have largely been younger, digital-first brands. “This is one reason the early adopters are often D2C brands with short decision cycles, like beauty, fashion and quick commerce, while large FMCG players watch, pilot, and wait for clearer models of business impact,” Sampath says.

A Mismatch With the FMCG Playbook

Chandramouli, CEO, TRA Research, believes the hesitation is rooted in how FMCG marketing fundamentally works. “FMCG brands are fundamentally built on scale, consistency, and repetition. Micro-dramas, while culturally buzzy, are still evolving as a format.”

The very nature of micro-dramas makes them difficult to standardise. “The storytelling is often emotionally rich but fragmented, platform-dependent, and hard to standardize, which makes it difficult for FMCG marketers to plug them into established media planning models that prioritize reach, frequency, and predictable ROI.”

There is also a reputational risk. “FMCG advertising traditionally operates in high-clarity environments where brand presence is unmistakable. Micro-dramas blur the line between content and commerce, and many brands are still cautious about integrating themselves into narratives where the product role isn’t immediately clear or could feel forced.”

But he, too, sees this as a matter of timing. “This isn’t a rejection; it’s a timing issue. FMCG brands tend to be fast followers, not first movers. Once micro-dramas mature into a more structured ecosystem with clearer measurement, repeatable formats, and proven brand lift, we’ll likely see adoption accelerate.”

A Format Still Finding Its Feet

Creators believe the medium itself is still evolving. Auteur producer Nilakshi Sengupta notes that there is a sharp difference between the kind of content being produced for micro-dramas and the storytelling standards of traditional entertainment. She argues that greater focus on stronger narratives and better production quality will be essential if mainstream brands are to take the format seriously.

Micro-dramas have clearly cracked consumer attention. They are addictive, fast-growing and increasingly mainstream. What they have not yet cracked is the confidence of India’s biggest advertisers.

FMCG brands need scale, safety and measurable returns. Micro-dramas, for all their buzz, are still fragmented, experimental and difficult to evaluate.For now, brands are watching from the sidelines – experimenting with sponsorships and subtle integrations, but stopping short of big-ticket advertising.

As Mathias puts it: marketers are not rejecting micro-dramas. They are simply waiting for the format to mature. And when it does, the ad money may finally follow.